Outing the Work of Art

Frederic Leighton,The Sluggard, 1885 — on display at The First Homosexuals exhibition at Chicago’s Wrightwood 659.

As scholars seek to liberate the personal lives of artists past, we must boldly meet our own ominous present

My partner and i hadn’t planned to take any big trips this year. But as fall unfolds before us, we’ll have made three epic artistic voyages so far.

All of our travels were tied to museum exhibitions: The First Homosexuals at Wrightwood 659 in Chicago; Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men at the Chicago Arts Institute; History is Painted by the Victors (Kent Monkman) at the Denver Art Museum; and Sargent in Paris and Superfine at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City.

Though these fantastic exhibits had different focuses, they presented an open and ongoing discussion around the repressed sexuality of art and artists of the past.

This trend in scholarship isn’t new. England’s Pallant House Gallery held an exhibition of Gay artist Glyn Philpot’s work in 2022. Tate Britain is showcasing Edward Burra.

But not everyone has been happy with these discussions. French art critics in particular rejected the questions posed in the Caillebotte show, blasting what they said was overemphasizing any homoerotic reading into the French artist’s work — despite the fact that so much of the lifelong bachelor’s work centered on the men around him, culminating in two very intimate, large male nudes that were so shocking at the time that they were rejected from shows. Indeed in the rejection commentary, barely veiled innuendos were made about the homoerotic nature of the pieces.

Of course we wish every amazing artist played for “our team,” and it’s important to keep our pink-colored retrospective glasses focused on the evidence as best we can. But the heterosexual world has a long tradition of stuffing artists in the closet with nary a historical thought.

Now that we’re living in another era of increased anti-LGBTQ+ state censorship, it’s even more important to continue these discussion and revisit the lives and works of the past while fighting for our Queer futures — like the White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney, which featuring an exhibition of contemporary LGBTQ+ art from heavily censored China.

Therein lies one of my favorite things about art: expressing yourself and engaging in an ongoing conversation that exists beyond the bounds of place and time.

And all four of the artists featured in Issue 2 of “Quarteros Review” are part of that discussion.

Take our cover artist Samuel Pettit, whose comic Jesus at the Drag Show went viral for calling out bigoted religious hypocrisy in our current time.

Or Jayson G. Ransome who has used his art as a means of exploring and finding himself in ways he couldn’t in the everyday world.

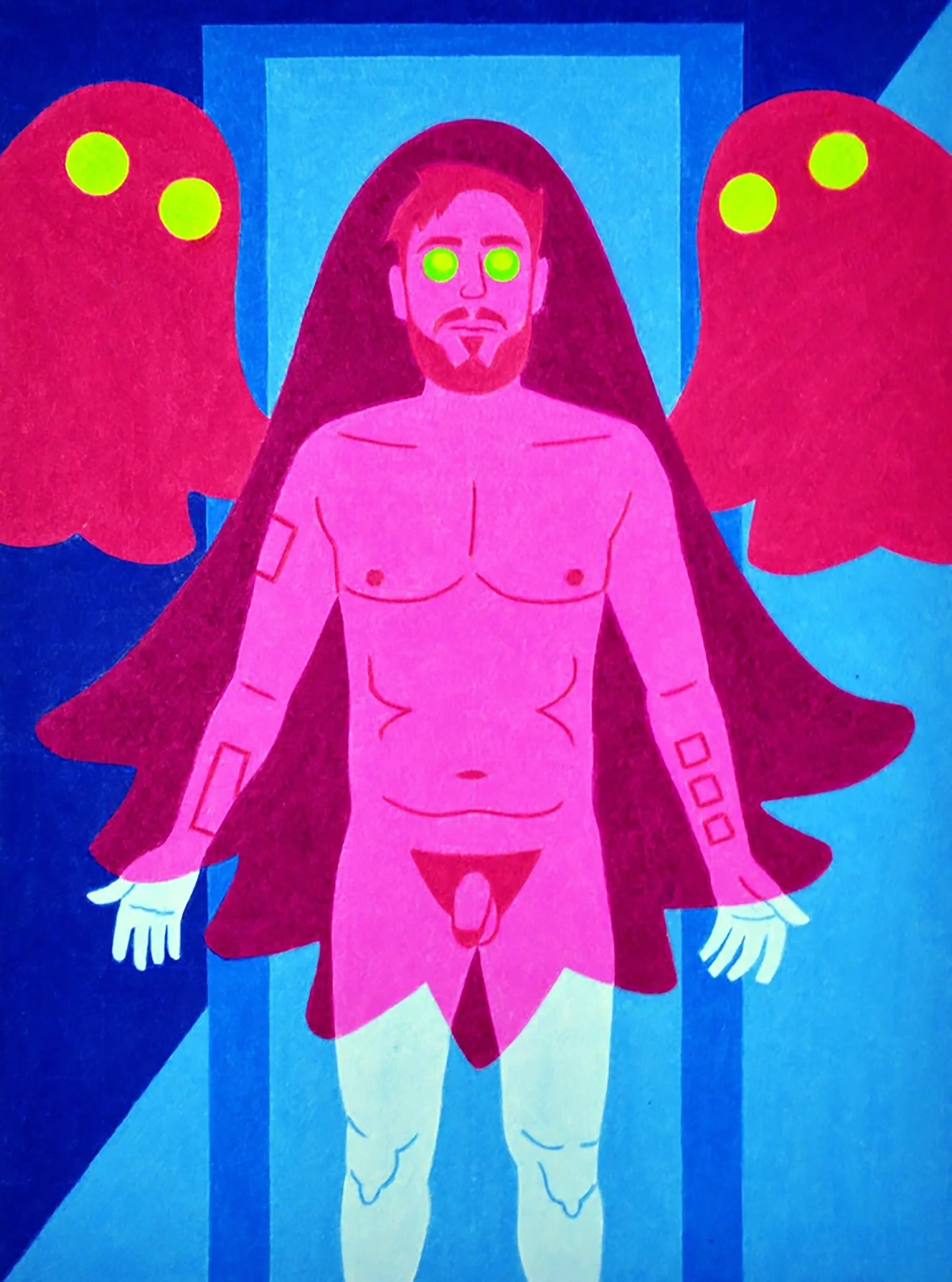

Ian Thomas Franks fearlessly uses his canvases to transport us to all kinds of glorious Gay worlds, while referencing all kinds of historical Queer culture — combining what has been and what could be.

And Casey Hannan is exploring what it is to be Gay/Queer in the Internet age through his graphically colorful drawings and sharp prose, blending the lines of what we think is private and what actually is — a particularly important topic as “security” technology continues to advance and invade all aspects of our lives.

Andreas Andersen, Interior with Hendrik Andersen and John Briggs Potter in Florence, 1894 — on display at The First Homosexuals exhibition at Chicago’s Wrightwood 659.

So what lessons can we learn?

As the groundbreaking First Homosexuals show demonstrated, Gay art and artists have always existed, and even if they didn’t have the words for their identity, they used their visual language, adapting to and challenging the social constraints in place at any given time to communicate it with the world.

We must be heartened by that knowledge and continue to push against those boundaries, even when it feels they are closing in.

Queer art culture has been strong and enduring, and it will continue to be so.

Be bold.

Be brave.

Be Gay.

And keep making your art every day.

Read all about it!

This editorial appeared in the second issue of “Quarteros Review,” a gay-art focused indie magazine produced by erostakles.

If you would like to purchase a PDF copy of any issue, you can find that here. Physical copies are also available via Blurb.